International Churches of Christ

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| International Churches of Christ | |

|---|---|

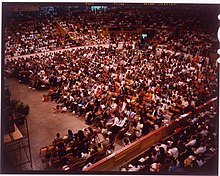

An International Church of Christ worship service | |

| Classification | Protestant[1] |

| Orientation | Restorationist |

| Polity | Congregationalist |

| Associations | |

| Region | Global (144 nations)[5][better source needed] |

| Official website | International Churches of Christ |

The International Churches of Christ (ICOC) is a body of decentralized, co-operating, religiously conservative and racially integrated Christian congregations.[6][better source needed][7] Originating from the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement, the ICOC emerged from the discipling movement within the Churches of Christ in the 1970s. Kip McKean, a key figure until 2003, expanded the church from Gainesville to Boston and it quickly became one of the fastest growing Christian movements with a heavy focus on US college campuses. Under his leadership, the ICOC experienced rapid growth but also faced criticism. In March 2024, the ICOC numbered their members at 112,000.[6][better source needed]

The ICOC is organized with a cooperative leadership structure broken down into regional families that have their own representative delegates. Viewing the Bible as the sole authority, the ICOC emphasizes being a non-denominational church united under Christ. It advocates salvation through faith and baptism, rejects "faith alone", and emphasizes global unity. Historically, the church practiced exclusive baptism and strict "discipling", but since 2002, has shifted to a more decentralized, voluntary discipling approach. The ICOC also promotes racial integration, opposes abortion and recreational drugs, and engages in international service through the HOPE Worldwide.

David V. Barrett noted in 2001 that in the 1990s the ICOC "attracted a huge amount of criticism and hostility" from the anti-cult movement. The church has been barred from recruiting students on campuses or has been denied student organization status at numerous universities.

History

[edit]Origins in the Stone-Campbell Movement

[edit]

The ICOC has its roots in a movement that reaches back to the period of the Second Great Awakening (1790–1870) of early nineteenth-century America. Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell are credited with what is today known as the Stone-Campbell or Restoration Movement. There are a number of branches of the Restoration movement, and the ICOC was formed from within the Churches of Christ.[8][9] Specifically, it was born from a discipling movement that arose among the Churches of Christ during the 1970s.[10] This discipling movement developed in the campus ministry of Chuck Lucas.[10]

In 1967, Chuck Lucas was minister of the 14th Street Church of Christ in Gainesville, Florida (later renamed the Crossroads Church of Christ). That year he started a new project known as Campus Advance (based on principles borrowed from the Campus Crusade and the Shepherding Movement). Centered on the University of Florida, the program called for a strong evangelical outreach and an intimate religious atmosphere in the form of soul talks and prayer partners. Soul talks were held in student residences and involved prayer and sharing overseen by a leader who delegated authority over group members. Prayer partners referred to the practice of pairing a new Christian with an older guide for personal assistance and direction. Both procedures led to "in-depth involvement of each member in one another's lives".[11]

The ministry grew as younger members appreciated the new emphasis on commitment and models for communal activity. This activity became identified by many with the forces of radical change in the larger American society that characterized the late sixties and seventies. The campus ministry in Gainesville thrived and sustained strong support from the elders of the local congregation in the 'Crossroads Church of Christ'. By 1971, as many as a hundred people a year were joining the church. Most notable was the development of a training program for potential campus ministers.[12]

From Gainesville to Boston: 1970s–1980s

[edit]Among the converts at Gainesville was a student named Kip McKean who was converted by Chuck Lucas.[3] McKean was introduced to the Florida Church of Christ's controversial recruitment style in 1967.[13] Born in Indianapolis,[14] McKean completed a degree while training at Crossroads, and afterward served as campus minister at several Churches of Christ locations. By 1979 his ministry grew from a few individuals to over three hundred making it the fastest growing Church of Christ campus ministry in America.[8][9] McKean then moved to Massachusetts, where he took over the leadership of the Lexington Church of Christ (soon to be called the Boston Church of Christ). Building on Lucas' initial strategies, McKean only agreed to lead the church in Lexington as long as every member agreed to be 'totally committed'. The church grew from 30 members to 3,000 in just over 10 years in what became known as the 'Boston Movement'.[8][9] McKean taught that the church was "God's true and only modern movement" and under his leadership, it "envisioned and implemented a tightly structured community that returned to the doctrines and lifestyles of the first-century Christian churches, with the goal of evangelizing the entire planet within a generation".[15] According to journalist Madeleine Bower, "the group became renowned for its extreme views and rigid teaching of the Bible, but mainstream churches quickly disavowed the group".[16]

David G. Bromley and J. Gordon Melton, sociologist and historian of religion respectively, note how International Churches of Christ grew quickly in the 1980s, but that "Even as ICOC developed, however, its relationships with several established institutional sectors deteriorated". The church's "doctrine signaled the movement's self-perceived superiority to other Christian churches in teaching that it alone had rediscovered biblical doctrines critical to individual salvation and insisting on rebaptizing new members to ensure their salvation". They note that further tensions developed as a result of the church's "aggressive evangelizing tactics" and use of 'discipling' or 'shepherding' practices, whereby new members were provided spiritual guidance and had their personal lives closely supervised by more established members. "Members were taught that commitment to the church superseded all other relationships", write Bromley and Melton. As a result, "the main branch of the Churches of Christ disavowed its relationship with ICOC; a number of universities banned ICOC recruiters; and ICOC became a prominent target of media and anticult group opposition".[17]

In 1985 a Church of Christ minister and professor, Dr. Flavil Yeakley, administered the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator test to the Boston Church of Christ (BCC), the founding church of the ICOC. Yeakley passed out three MBTI tests, which asked members to perceive their past, current, and five-year in the future personality types.[18][19][20] While over 900 members were tested, 835 individuals completed all three forms. A majority of those respondents changed their perceived or imagined personality type scores on the three tests in convergence with a single type.[18][19] After completing the study, Yeakley observed that "The data in this study of the Boston Church of Christ does not prove that any certain individual has actually changed his or her personality in an unhealthy way. The data, however, does prove that there is a group dynamic operating in that congregation that influences its members to change their personalities to conform to the group norm".[21]

By the end of 1988 the churches in the Boston Movement were for all practical purposes a distinct fellowship, initiating a fifteen-year period during which there would be little contact between the CoC and the Boston Movement. By 1988, McKean was regarded as the leader of the movement.[12] It was at this time that the Boston church initiated its program of outreach to the poor called HopeWorldwide.[citation needed] Also in 1988, McKean selected a handful of couples that he and Elena, his wife, had personally trained and named them World Sector Leaders.[22] In 1989 mission teams were officially sent out to Tokyo, Honolulu, Washington, DC, Manila, Miami, Seattle, Bangkok, and Los Angeles. That year, McKean and his family moved to Los Angeles to lead the new church "planted" (a euphemism the church uses for "established")[23] some months earlier. Within a few years Los Angeles, not Boston, was the fulcrum of the movement.[12]

The ICOC: 1990s

[edit]

In 1990 the Crossroads Church of Christ broke with the movement and, through a letter written to The Christian Chronicle, attempted to restore relations with the Churches of Christ.[10]: 419 By the early 1990s some first-generation leaders had become disillusioned by the movement and left.[10]: 419 The movement was first recognized as an independent religious group in 1992 when John Vaughn, a church growth specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary, listed them as a separate entity.[8][12] TIME magazine ran a full-page story on the movement in 1992 calling them "one of the world's fastest-growing and most innovative bands of Bible thumpers" that had grown into "a global empire of 103 congregations from California to Cairo with total Sunday attendance of 50,000".[24] A formal break was made from the Churches of Christ in 1993 when the group organized under the name "International Churches of Christ."[10]: 419 This new designation formalized a division that was already in existence between those involved with the Crossroads/Boston Movement and "original" Churches of Christ.[10]: 418 [25] In September 1995, the Washington Post reported that for every three members joining the church, two left, attributing this statistic to church officials.[26]

Growth in the ICOC was not without criticism.[citation needed] Other names that have been used for this movement include the "Crossroads movement," "Multiplying Ministries," and the "Discipling Movement".[11] One Church is formed per city, and as it expands it is broken down into "sectors" that oversee "zones" which have their own neighborhood Bible study groups. Claims that this structure too authoritarian were responded to by McKean saying, "I was wrong on some of my initial thoughts about biblical authority".[27] Al Baird, former ICOC spokesperson adds, "It's not a dictatorship," ; "It's a theocracy, with God on top."[24] The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported in 1996 that "The group is considered so aggressive and authoritarian in its practices that other evangelical Protestant groups have labeled it 'aberrational' and 'abusive'. It has been repudiated by the mainstream Churches of Christ, a 1.6 million-member body from which it grew".[28]

Growth continued globally and in 1996 the independent organisation "Church Growth Today" named the Los Angeles ICOC as the fastest growing Church in North America for the second year running and another eight ICOC churches were in the top 100.[8][29] By 1999, the Los Angeles church reached a Sunday attendance of 14,000.[12] By 2001, the ICOC was an independent worldwide movement that had grown from a small congregation to 125,000 members and had planted a church in nearly every country of the world in a period of twenty years.[8][29] In his 2001 book The New Believers: A Survey of Sects, 'Cults' and Alternative Religions, David V. Barrett wrote that the ICOC was "currently causing perhaps more concern than almost any other" evangelical church in the United Kingdom.[30] Barrett writes that "In the last decade ICOC has attracted a huge amount of criticism and hostility from anti-cultists", noting that it had been made aware of various criticisms "but unlike some of the other movements founded in the 1970s, does not yet have appeared to reached the point in its development where it becomes sensitive to the genuine distress of some of its members and their families have experienced, and willing to modify some of its practices to reduce the possibility of causing such distress".[31] In 1998, Ron Loomis, an expert on cults and leader of a cult-awareness program at the College of Lake County, called the ICOC "the most intensive cult in existence since the mid-1970s".[32]

Barrett also noted in 2001 that as with other new religious movements, membership turnover in the ICOC was high, with "many leaving after a few months because they find the discipline of life in the movement too demanding or oppressive". He concluded that "There are probably far more ex-members of ICOC than current members", though noted ICOC attempts to discourage members from leaving and that communal living arrangements and the fact that the ICOC encouraged the breaking-off of friendships with non-members made it difficult for some to leave.[33]

The ICOC: 2000s

[edit]Membership growth stopped as the 90's finished.[34] In 2000, the ICOC announced the completion of its six-year initiative to establish a church in every country with a city that had a population over 100,000.[22][35] In spite of this, numerical growth continued to slow. Beginning in the late 1990s, problems arose as McKean's moral authority as the leader of the movement came into question.[8][9] Expectations for continued numerical growth and the pressure to sacrifice financially to support missionary efforts took its toll. Added to this was the loss of local leaders to new planting projects. In some areas, decreases in membership began to occur.[12] At the same time, realization was growing that the accumulated costs of McKean's leadership style and associated disadvantages were outweighing the benefits. In 2001, McKean's leadership weaknesses were affecting his family, with all of his children disassociating themselves from the church, and he was asked by a group of long-standing elders in the ICOC to take a sabbatical from overall leadership of the ICOC. On 12 November 2001, McKean, who had led the International Churches of Christ, issued a statement that he was going to take a sabbatical from his role of leadership in the church:

During these days Elena and I have been coming to grips with the need to address some serious shortcomings in our marriage and family. After much counsel with the Gempels and Bairds and other World Sector Leaders as well as hours of prayer, we have decided it is God's will for us to take a sabbatical and to delegate, for a time, our day-to-day ministry responsibilities so that we can focus on our marriage and family.

Nearly a year later, in November 2002 he resigned from the office and personally apologized citing arrogance, anger and an over-focus on numerical goals as the source of his decision.[8][9]

Referring to this event, McKean said:

This, along with my leadership sins of arrogance, and not protecting the weak caused uncertainty in my leadership.[36]

Ronald Enroth writes that McKean "was forced to step down because of his own rule that leaders must resign if their children leave the church".[37]

The period following McKean's departure included a number of changes in the ICOC, including decentralization and a dismantling of its headquarters and central leadership.[38] Some changes were initiated from the leaders themselves and others brought through members.[8][39] Most notable was Henry Kriete, a leader in the London ICOC, who circulated an open letter detailing his feelings about theological exclusivism and authority in the ICOC. This letter affected the ICOC for the decade after McKean's resignation.[8][39] Christianity Today reported in 2003 that following McKean's resignation, "leadership now is in the hands of 10 elders ruling by consensus".[40]

Critics of the ICOC claim that Kip McKean's resignation sparked numerous problems.[41] However, others have noted that since McKean's resignation the ICOC has made numerous changes. The Christian Chronicle, a newspaper for the Churches of Christ, reports that the ICOC has changed its leadership and discipling structure. According to the paper, "the ICOC has attempted to address the following concerns: a top down hierarchy, discipling techniques, and sectarianism".[3] In September 2005, nine members were elected to serve as a Unity Proposal Group. They subsequently developed a 'Plan for United Cooperation', published in March 2006.[42] In September 2012, it was reported that around 93% of ICOC churches supported the plan.[3]

Over time, McKean attempted to re-assert his leadership over the ICOC, yet was rebuffed. Sixty-four Elders, Evangelists and Teachers wrote a letter to McKean expressing concern that there had been "no repentance" from his publicly acknowledged leadership weaknesses.[43] McKean then began to criticize some of the changes that were being made, as he did in the 1980s toward Mainline Churches of Christ.[44] After attempting to divide the ICOC he was disfellowshipped in 2006[44][45] and founded a church that he called the International Christian Church.[44]

The Christian Chronicle reports that the ICOC's reported membership peaked at 135,000 in 2002, before dropping to 89,000 in 2006. ICOC leaders reported that a mid-2012 survey revealed that membership had grown again to 97,800 members in 610 churches across 148 countries.[3]

Legal issues

[edit]Lawsuit by an ICOC member church alleging defamation

[edit]On November 23, 1991, two Singapore Newspapers, The New Paper (English) and Lianhe Wanbao (Chinese), published articles stating that the Singapore Central Christian Church (a member of ICOC) was a "cult". The church sued the papers, alleging defamation. An initial court ruling held that what the papers had written was fair and in the public interest. An appeals court, however, overruled the lower court, stating that the papers had stated that the church was a cult as if that was a fact, when it was not a fact, but a comment. The papers were each ordered to pay the church S$20,000. The New Paper had to pay the founder of the church, John Philip Louis, S$30,000. The papers also had to pay the legal fees of the church and its founder.[46] In the same ruling, the appeals court held that an article that had also characterized the church as a cult, in the bi-monthly, Singapore-based, Christian magazine Impact, was written fairly from the standpoint of a Christian publication written for the Christian community. The church and Louis were ordered to pay Impact's legal fees.[46]

Lawsuits related to alleged coverup of sexual abuse

[edit]In 2022, the ICOC and the International Christian Churches were named in multiple US federal lawsuits. They alleged that between 1987 and 2012, leaders of the two churches covered up the sexual abuse of children, some of whom were as young as three, and financially exploited members.[47][48] The lawsuits alleged that the ICOC, together with its affiliates the International Christian Church, the City of Angels International Christian Church, HOPE Worldwide and Mercy Worldwide, "indoctrinated" the plaintiffs, keeping them isolated while they were sexually exploited and manipulated through the ICOC's "rigid" belief system. The lawsuit also named ICOC leaders, founder Kip McKean and the estate of Chuck Lucas, as defendants. The plaintiffs alleged that the ICOC and its leaders created a "system of exploitation that extracts any and all value it can from members". The lawsuits alleged that members were forced to give 10% of their income as a tithe to the church and additionally to fund twice-yearly special mission trips, which drove some to depression and suicide.[49] The Los Angeles ICOC responded to the lawsuits by stating: "As the Church's long-standing policies make clear, we do not tolerate any form of sexual abuse, sexual misconduct, or sexual coercion, and we will fully cooperate with the authorities in any investigations of this type of behavior".[47] The lawsuits were voluntarily dismissed by the plaintiffs in July 2023.[50]

Church governance

[edit]

This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (September 2024) |

The International Churches of Christ are a family of over 750 independent churches in 155 nations around the world. The 750 churches form 34 Regional Families of churches that oversee mission work in their respective geographic areas of influence. Each regional family of churches sends Evangelists, Elders and Teachers to an annual leadership conference, where delegates meet to pray, plan and co-operate world evangelism.[51][52] "Service Teams" provide global leadership and oversight.[citation needed] The Service Teams consists of an Elders, Evangelists, Teachers, Youth & Family, Campus, Singles, Communications & Administration, and HOPEww & Benevolence teams.[51]

Ministry Training Academy

[edit]This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (September 2024) |

The education and ministerial training program in the ICOC is the Ministry Training Academy (MTA). In 2013, the MTA finalized a curriculum consisting of twelve core courses that are divided into three areas of study: biblical knowledge, spiritual development, and ministry leadership. Each course requires at least 12 hours of classroom study in addition to course work. An MTA student who completes the twelve core classes receives a certificate of completion.[53]

ICOC's relationship with mainstream Churches of Christ

[edit]With the resignation of McKean, some efforts at healing between the International Churches of Christ and the mainstream Churches of Christ are being made. In March 2004, Abilene Christian University held the "Faithful Conversations" dialog between members of the Churches of Christ and International Churches of Christ. Those involved were able to apologize and initiate an environment conducive to building bridges. A few leaders of the Churches of Christ apologized for use of the word "cult" in reference to the International Churches of Christ.[3] The International Churches of Christ leaders apologized for alienating the Churches of Christ and implying they were not Christians.[3] Despite improvements in relations, there are still fundamental differences within the fellowship.[54][needs update] Early 2005 saw a second set of dialogues with greater promise for both sides helping one another.[citation needed]

HOPE Worldwide

[edit]Founded in 1991, HOPE Worldwide is a non-profit organization established by the ICOC that supports disadvantaged children and the elderly. It relies on donations from ICOC churches, companies and individuals and on government grants.[55][56] As of September 1997[update], HOPE Worldwide was operating 100 projects in 30 countries.[57] As of 2023[update], the organization reported serving on average more than one million people per year, in more than 60 countries.[58]

HOPE Worldwide received grants from US president George W. Bush's AIDS program for its work in several countries, and arranged for Chris Rock to visit South Africa for an AIDS prevention event.[2]

Beliefs and practices of the ICOC

[edit]Beliefs

[edit]This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (April 2024) |

The ICOC considers the Bible the inspired word of God. Through holding that their doctrine is based on the Bible alone, and not on creeds and traditions, they claim the distinction of being "non-denominational". Members of the International Churches of Christ generally emphasize their intent to simply be part of the original church established by Jesus Christ in his death, burial, and resurrection, which became evident on the Day of Pentecost as described in Acts 2.[59][better source needed] They believe that anyone who follows the plan of salvation as laid out in the scriptures is saved by the grace of God, through their faith in Jesus, at baptism.[6][better source needed] The ICOC has over 700 churches spread across 155 nations, with each church being a racially integrated congregation made up of a diversity of people from various age groups, economic, and social backgrounds. They believe Jesus came to break down the dividing wall of hostility between the races and people groups of this world and unite mankind under the Lordship of Christ [6][better source needed]

Like the Churches of Christ, the ICOC recognizes the Bible as the sole source of authority for the church and it also believes that the current denominational divisions are inconsistent with Christ's intent, believing instead that Christians ought to be united.[citation needed] The ICOC, like the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), in contrast to the CoC, consider permissible practices that the New Testament does not expressly forbid.[60]

The ICOC teaches that "anyone, anywhere who follows God's plan of salvation in the Bible and lives under the Lordship of Jesus, will be saved. Christians are saved by the grace of God, through their faith in Jesus Christ, at baptism."[6][better source needed] They claim that "faith alone" (e.g., saying the Sinner's Prayer) is not sufficient unless an individual by faith obeys God and gets baptized, believing that baptism is necessary for the forgiveness of sins. [3][61][better source needed] The belief in the necessity of baptism is in agreement with the prevailing view in the Churches of Christ and Restoration Movement.[62] It is in contrast with the beliefs of Baptist churches that teach that faith alone is adequate for salvation.[63][64]

One True Church (OTC) doctrine

[edit]Originally, the ICOC taught that only baptisms within ICOC member churches were legitimate and hence only members of ICOC churches had had their sins forgiven and were saved. This is known as the One True Church (OTC) doctrine.[65]

In 2003, however, after the departure of McKean, the leadership of ICOC issued letters of apology stating that they had been "too judgmental" in applying this doctrine. As a consequence, many within ICOC began to accept that baptisms outside of ICOC churches, particularly those of family members who belonged to other Christian denominations, could be legitimate.[61][better source needed] [66]

This is consistent with their historical roots in the Churches of Christ, which believe that Christ established only one church, and that the use of denominational creeds serves to foster division among Christians.[67]: 23, 24 [68][69] This belief dates to the beginning of the Restoration Movement; Thomas Campbell expressed an ideal of unity in his Declaration and address: "The church of Jesus Christ on earth is essentially, intentionally, and constitutionally one."[70]: 688

Lifestyle beliefs

[edit]The ICOC is opposed to abortion, recreational drugs, and non-marital sexual relations. Homosexuals are welcome, but they must lead a life of chastity.[71] Members' romantic partners require approval by the church.[16]

Practices

[edit]

Sunday worship

[edit]A typical Sunday morning service involves singing, praying, preaching, and the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. An unusual element of ICOC tradition is the lack of established church buildings. Congregations meet in rented spaces: hotel conference rooms, schools, public auditoriums, conference centers, small stadiums, or rented halls, depending on the number of parishioners. Though the church is not static, neither is it ad hoc – the leased locale is converted into a worship facility. "From an organizational standpoint, it's a great idea", observes Boston University Chaplain Bob Thornburg. "They put very little money into buildings...You put your money into people who reach out to more people in order to help them become Christians."[72]

This practice of not owning buildings changed when the Tokyo Church of Christ became the first ICOC church to build its own church building.[citation needed] This building was designed by the Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki.[73] This became an example for other ICOC churches to follow.[citation needed]

Discipling

[edit]McKean era (1979–2002)

[edit]A distinguishing feature of the ICOC under McKean was an intense form of discipleship. McKean's mentor, evangelist Chuck Lucas, developed this practice based in part on the book "The Master Plan of Evangelism" by Robert Coleman. Coleman's book taught that "Jesus controlled the lives of the apostles, that Jesus taught the apostles to 'disciple' by controlling the lives of others, and that Christians should imitate this process when bringing people to Christ."[74] Under McKean, "discipling" entailed members being "assigned a more senior adviser who is always available and frequently present in their lives, even at intimate moments, which mentors them through relationship difficulties. In this practice, individuals interact with other group members in hierarchical relationships".[75] According to Kathleen E. Jenkins's ethnography of the church, McKean viewed discipling as "the most efficient way to achieve the movement's stated goal: 'to evangelize the world in one generation'".[76]

The church's emphasis on discipling during this period was the subject of criticism. A number of ex-members expressed problems with discipling in the ICOC.[77] Critics and former members allege that discipling "involved public scorn as a way to humiliate vulnerable members, to keep them humble".[78] Jenkins notes that "[t]his ICOC structure has been greatly criticized by anti-cult organizations, university officials (the ICOC has been banned from several campuses), and ex-members".[7]

Discipling under McKean was mandatory. All disciples (i.e., baptized members) had to be paired with and mentored by a more mature Christian . They had to check in with their discipler frequently, such as daily or weekly, and was held accountable by them. This included the activities and Church contribution a disciple would give (typically 15-30% including "special contribution) .[79] Disciples were also held accountable for how many new people they met on a daily basis and recruited into the church. Anyone criticizing the authority of a discipler was publicly rebuked in group meetings.[80]

Those who left the ICOC were to be shunned,[81] and disciples were told that only those baptized within the ICOC were saved; all other people were damned. Furthermore, anyone that left the church would also lose their salvation.[82]

A 1999 study found that a substantial minority of former ICOC members included in the study "reached clinically significant levels of psychological distress, depression, dissociation, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms". Two-thirds of them had sought psychotherapy after leaving the church.[83]

Nonetheless, many disciples, including some who left, got a great deal out of the structure of the discipling system. The found "meaning and community" and formed close friendships across racial and class lines within the ICOC.[84] Sociologist Dr. Joseph E. Lee posits that the strict discipling program helped lead to a lowering of barriers between races and classes. He found this to be a general characteristic of organizations (e.g., martial arts schools) with strong formal beliefs and discipline.[85][86] Kathleen Jenkins found that "Discipling [...] created tightly bound networks that threw members into frequent contact with disciples from different backgrounds who intimately and routinely intervened in all aspects of an individual's life. These intimate racially and ethnically diverse discipling networks provided members with social resources such as childcare, teen counseling, tutoring, employment opportunities, domestic help, and other kinds of assistance in day-to-day living".[7]

Post McKean era (2002–present)

[edit]According to Joseph Yi, writing in 2009, with the departure of McKean in 2002 the ICOC transitioned from a top-down organization to a "loose federation of autonomous local churches".[87] This led to a change in discipling practices. One of the local ICOC churches, the Chicago Church of Christ, made discipling voluntary and not mandatory. Instead of a top-down hierarchy, they adopted a "servant leadership" model.[87]

Love bombing

[edit]The ICOC has been accused of using the tactic of "love bombing",[88][89][90][91][92] which David Barrett describes as "showing a great deal of love, affection and attention to prospective members to draw them in", resulting in the criticism that "vulnerable or lonely people, and this includes many students, will be attracted by this".[93] Journalist Alasdair Belling has noted that this attention and praise "slowly becomes more conditional over time".[90]

University campuses

[edit]

Starting from his own college days in the 1970s, McKean and the churches he has led (e.g., ICOC and its predecessors and successors) made recruiting on college campuses a priority.[94]

In 1994, the New York Times reported that Campus Advance, the ICOC's campus ministry, had been accused of using "high-pressure tactics" to "systematically target and isolate recruits and deprive them of food and sleep in carefully coordinated steps to break down resistance and cause mental confusion", saying former members compared the group's tactics to those of a cult.[89] In response, a spokesperson for the New York Church of Christ stated that "This word 'cult' is so inflammatory and thrown around so loosely that it is completely unfair and totally unfounded". The articles noted that "representatives of the church say their actions are misrepresented by religious groups jealous of their ability to appeal to young adults". The New York Times noted that "complaints against the church and its campus affiliates are strikingly uniform in portraying church members as adept in singling out vulnerable targets, like lonely students, and enveloping them rapidly with a psychological dependency that is difficult to break", while the Church leaders rejects nearly every allegation.[89]

In 1996 the dean of Boston University's Marsh Chapel, Rev. Robert Watts Thornburg, referred to the church as "the most destructive religious group I've ever seen". Thornburg stated that the church's "[r]ecruitment techniques include the duplicitous use of love and high pressure harassment, producing incredibly high levels of false guilt" and that "The group cuts across the very core of what higher education is about. It refuses to receive questions or have any kind of discussion of an idea. It simply says 'Believe and obey', and if you do anything else you are hard of heart". An evangelist for the church responded to the allegations by stating that "We are a very, very different church from what's already established" and that "Whenever you see something radical or different, of course you're going to get that label that it's a cult".[95]

In 2000, a U.S. News & World Report article by Carolyn Kleiner on proselytizing on college campuses described the ICOC as a "fast-growing Christian organization known for aggressive proselytizing to college students" and as "one of the most controversial religious groups on campus". Kleiner states that "some ex-members and experts on mind-control assert [it] is a cult". The article quotes ICOC spokesperson Al Baird, who stated "We're no more a cult than Jesus was a cult", and sociologist Jeffrey K. Hadden, who was in agreement with Baird and stated that "every new religion experiences a high level of tension with society because its beliefs and ways are unfamiliar. But most, if they survive, we come to accept as part of the religious landscape".[96]

A 2004 edition of the Encyclopedia of Evangelism reported that academics had complained that their students who get involved with the group tend to lose interest in their studies.[97]

Anna Kira Hippert and Sarah Harvey of the Religion Media Centre noted in 2021 that the ICOC's discipling system together with its university campus activities "made the ICOC one of the more controversial new Christian groups in the UK".[98]

University responses

[edit]Boston University banned the group in 1987[95] or 1989, by which time 50 students per year were reportedly dropping out of education to join the church.[99] The ICOC was reportedly the first religious group to have been banned at Boston University.[100]

In 1994 it was banned at American University and George Washington University.[89]

In November 1996, it was reported that the ICOC had either been barred from recruiting students or had been denied student organization status by 22 US colleges and universities, according to information compiled by the American Family Foundation. The reasons cited for these decisions were mostly accusations of harassment or violations of campus policies.[101]

In 1998, it was reported that the ICOC had been banned from university campuses in the United Kingdom, including in London, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Manchester.[102]

In March 2000, the State University of New York at Purchase settled a court case about an incident that happened in 1998, when it had suspended an ICOC member was for allegedly "intimidating ... harassing ... and detaining" another student and banned the church from holding services on the Purchase campus. The student was reinstated and the ICOC was allowed to use campus facilities again.[96]

By 2000, according to US News & World Report, "[a]t least 39 institutions, including Harvard and Georgia State, [had] outlawed the organization at one time or another for violating rules" regarding recruiting and harassment.[96]

The ICOC in the 2020s was banned from operating at a number of Australian universities.[16][90] The ICOC's group at the University of New South Wales (where it is formally banned), the UNSW Lions, has repeatedly renamed itself to maintain a presence on campuses.[90]

Racial integration in ICOC churches

[edit]ICOC churches have an overall higher degree of racial integration than many other religious congregations. This is a priority for the denomination. Racial prejudice is viewed as a state of personal sinfulness which is done away with once a person is baptized and becomes a member. Jenkins also notes that "mandatory close and frequent social interaction forced members to develop such strong cross-racial and ethnic networks".[7] Writing in 2004, Kevin S. Wells reported that "The fact that ICOC congregations are typically multicultural has [...] gained the positive attention of national media in recent years".[103] In 2017, the ICOC formed an organization called SCUAD (Social, Cultural, Unity. and Diversity) that would "seek to champion racial conversation, education, and action among ICOC churches" [104][better source needed] By 2021, many local ICOC churches had instituted their own SCUAD groups. There was, however, a certain amount of backlash from members who saw the SCUADs' explicit discussion of racism as a form of critical race theory. Nonetheless, by 2022 most congregations had begun conversations about "racial inclusion, diversity and justice", although Michael Burns states that "It seemed [...] that very few had undertaken to carefully examine their history, beliefs, practices, and systems and subsequently engaged in significant structural change".[104][better source needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ “Though some in the Movement have been reluctant to label themselves Protestants, the Stone-Campbell Movement is in the direct lineage of the Protestant Reformation. Especially shaped by Reformed theology through its Presbyterian roots, the Movement also shares historical and theological traits with Anglican and Anabaptist forebears." Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Protestant Reformation", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8

- ^ a b "Religious groups getting more AIDS funding". NBC News. The Associated Press. 31 January 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ross Jr, Bobby (September 2012). "Revisiting the Boston Movement: ICOC growing again after crisis". christianchronicle.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "IP > Featured Items". ipibooks.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- ^ "Leadership". 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "About the ICOC". "Disciples Today" – official ICOC web site. 18 February 2016. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Jenkins, Kathleen E. (2003). "Intimate Diversity: The Presentation of Multiculturalism and Multiracialism in a High-Boundary Religious Movement". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 42 (3): 393–409. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.00190. JSTOR 1387742.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stanback, Foster (1 January 2005). Into All Nations (A History of the I.C.O.C.). Illumination Publishers Intern. ISBN 9780974534220.

- ^ a b c d e Stockman, Farah (17 May 2003). "A Christian community falters". The Boston Globe. p. A1, A4. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Foster, Douglas Allen; Dunnavant, Anthony L. (2004). The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802838988., 854 pages, entry on International Churches of Christ

- ^ a b c Paden, Russell (July 1995). "The Boston Church of Christ". In Miller, Timothy (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 133–36. ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, John F. (2010). "The International Churches of Christ:A Historical Overview". Leaven:Vol 18:Iss. 2, Article 3. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Stanczak 2000, p. 114.

- ^ "Kipmckean.com – Get Your Answers Here!". Kip McKean. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- ^ Bromley, David G. (2021). "Sources of Challenge to Charismatic Authority in Newly Emerging Religious Movements". Nova Religio. 24 (4): 26–40. doi:10.1525/nr.2021.24.4.26.

- ^ a b c Bower, Madeleine (26 March 2023). "Inside NSW's most bizarre religious sects". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Bromley, David G.; Melton, J. Gordon (2012). "Reconceptualizing Types of Religious Organization". Nova Religio. 15 (3): 4–28. doi:10.1525/nr.2012.15.3.4.

- ^ a b Langone, Michael (1993). "1". Recovery from Cults. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. p. 39. ISBN 9780393701647.

- ^ a b Gasde, Irene; Richard A. Block (1998). "Cult Experience: Psychological Abuse, Distress, Personality Characteristics, and Changes in Personal Relationships". Cultic Studies Journal. 15 (2): 58. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Yeakley, Flavil (1988). The Discipling Dilemma. Gospel Advocate Company. ISBN 0892253118. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Brief History of the ICOC". KipMcKean.com. 6 May 2007. Archived from the original on 20 June 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Barbeliuk, Mark (May 1996). "The Church That's Brainwashing Australians". Reader's Digest.

- ^ a b Ostling, Richard N. (18 May 1992). "Keepers of the Flock". Time. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ "Campus Crusaders: The fast-growing International Churches of Christ welcomes students with open arms. Does it let them go?". Washington Post. 3 September 1995. p. F1, 4–5. ProQuest 903450905

- ^ Davis, Blair J. (March 1999). "The Love Bombers". Philadelphia City Paper. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ "Some call sect 'abusive'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 17 November 1996. p. A20. ProQuest 391759338

- ^ a b Saltenstall, Dave (22 October 2000). "A Church of Christ or Cult of Cash". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 230.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 233.

- ^ Przygoda, Mary Jo (20 November 1998). "Student shares how one group lured him during college years". Daily Herald. p. 1. ProQuest 309882181.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 232.

- ^ Taliaferro, Mike (30 January 2013). "Has a New Era Begun for the ICOC?". disciplestoday.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ McKean, Kip (4 February 1994). "Evangelization Proclamation" (PDF). International Churches of Christ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ McKean, Kip (21 August 2005). "The Portland Story". Portland International Church of Christ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Enroth, Ronald M. (2005). "What is a new religious movement?". In Enroth, Ronald M. (ed.). A Guide to New Religious Movements. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. pp. 9–25. ISBN 0830823816.

- ^ Chryssides & Wilkins 2014, p. 422.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2005, p. 240-246.

- ^ Kennedy, John W. (June 2003). "'Boston Movement' Apologizes: Open letter prompts leaders of controversial church to promise reform". Christianity Today. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Callahan, Timothy (1 March 2003). "Boston movement' founder quits". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Plan for United Cooperation" (PDF). International Churches of Christ. 11 March 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Brothers the ICOC. "Brothers' Letter to Kip McKean". disciplestoday.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Carrillo, Robert (2009). "The International Churches of Christ (ICOC)". Leaven. 17 (3). Pepperdine University. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ Brothers the ICOC. "Brothers' Statement to Kip McKean". disciplestoday.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b Jin, Lim Seng (1 September 1998). "Church wins appeal in libel case". The Straits Times. p. 26. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ a b Yeung, Ngai; Moskow, Sam (28 February 2023). "Church leaders concealed sexual abuse of young children, lawsuits allege". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Borecka, Natalia (19 March 2023). "US Christian group accused of covering up sexual abuse of minors". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Blair, Leonardo (4 January 2023). "International Churches of Christ abused, pressured members financially to the point of suicide: lawsuit". The Christian Post. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ "Five Women Sue Christian Organization Alleging Cover-up of Child Sexual Abuse – MinistryWatch". Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ a b Lamb, Roger (2015). "International Churches of Christ (ICOC) Co-operation Churches – ICOC Service Teams". icocco-op.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "International Churches of Christ (ICOC) Co-operation Churches". icocco-op.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ "ICOC Ministry Training Academy Guidelines". ICOC Ministry Training Academy. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "ICOC, 'mainline' leaders meet at Abilene Christian". The Christian Chronicle. 28 October 2005. Archived from the original on 4 January 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Kline, Mitchell (22 June 2005). "The Nashville Church forces members to donate, suit says". The Tennessean. p. B.1. ProQuest 239758349.

- ^ "Volunteers promote free health tests". Daily Press. 27 April 2002. p. C3. ProQuest 343139656.

- ^ Frame, Randy (1 September 1997). "The Cost of Discipleship? Despite allegations of abuse of authority, the International Churches of Christ expands rapidly". Christianity Today. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Did You Know? 5 Facts to Inspire Greater Hope..." (PDF). HOPE Worldwide. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Acts 2

- ^ William E. Tucker; Lester G. McAlister (1975). Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Chalice Press. pp. 242–247. ISBN 9780827217034.

- ^ a b Ferguson, Gordon (2 December 2009). "Baptismal Cognizance: What do you need to know when you are baptized?". Disciples Today (official ICOC web site). Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, ed. (2004). The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8. ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8

- ^ DeBerg, Jennifer (5 April 2023). "Family Caregivers of Older Adults Transitioning from Hospital to Home (ProQuest Dissertations and Theses)". doi:10.1079/searchrxiv.2023.00199. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Family Trees | US Religion". www.thearda.com. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Jenkins 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Jenkins 2005, p. 243.

- ^ V. E. Howard, What Is the Church of Christ? 4th Edition (Revised) Central Printers & Publishers, West Monroe, Louisiana, 1971

- ^ O. E. Shields, "The Church of Christ," Archived 29 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Word and Work, VOL. XXXIX, No. 9, September 1945.

- ^ J. C. McQuiddy, "The New Testament Church", Gospel Advocate (11 November 1920):1097–1098, as reprinted in Appendix II: Restoration Documents of I Just Want to Be a Christian, Rubel Shelly (1984)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, "Slogans", in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8,

- ^ Yi 2009, p. 75.

- ^ David Frey (July 1999). "The Fear of God: Critics Call Thriving Nashville Church a Cult". InReview Online.

- ^ Tokyo Church of Christ Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine page on the McGill University website (accessed 21 February 2011)

- ^ Daniel Terris (8 June 1986). "Come All Ye Faithful". The Boston Globe. p. 42. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Neitz, Mary Jo (2007). "Review of "Awesome Families: The Promise of Healing Relationships in the International Churches of Christ"" (PDF). Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews. 36 (1): 53–54. doi:10.1177/009430610703600131. JSTOR 20443664.

- ^ Jenkins 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Giambalvo, Carol (1997). The Boston Movement: Critical Perspectives on the International Churches of Christ. American Family Foundation. p. 219. ISBN 0931337062.

- ^ Bratcher, Drew (1 July 2008). "Unanswered Prayers: The Story of One Woman Leaving the International Church of Christ". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Yi 2009, p. <<60-62>>.

- ^ Yi 2009, p. 75-76.

- ^ Jenkins 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Yi 2009, p. 75–78.

- ^ Malinoski, Peter T.; Langone, Michael D.; Lynn, Steven Jay (1999). "Psychological distress in former members of the International Churches of Christ and noncultic groups". Cultic Studies Journal. 16 (1): 33–51.

- ^ Yi 2009, p. 78.

- ^ Yi 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Yi, Joseph (2015). "The Dynamics of Liberal Indifference and Inclusion in a Global Era". Society. 52 (3): 264–274. doi:10.1007/s12115-015-9897-z.

- ^ a b Yi 2009, p. 79.

- ^ Vogt, Amanda (19 April 1997). "A mainstream mask on fringe cults". Chicago Tribune. pp. N1-2. ProQuest 2278691113.

- ^ a b c d Nordheimer, Jon (30 November 1994). "Ex-Members Compare Campus Ministry to a Cult". New York Times. p. B.1. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024. ProQuest 429938522.

- ^ a b c d Belling, Alasdair (16 May 2022). "Sydney student shares warning signs after his friend joined a religious cult". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Guggenheim, Ken (25 September 1994). "Church's Membership Rises; So Does Criticism". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Indelicato, Isabelle (16 March 2021). "In Plain Sight: A Controversial Faith Group Finds a Home at Simmons". The Simmons Voice. Archived from the original on 20 September 2024. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 231.

- ^ Daniel Terris (8 June 1986). "Come All Ye Faithful". The Boston Globe. p. 13. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b Geraghty, Mary (13 December 1996). "Recruiting tactics of a religious group stir campus concerns". Chronicle of Higher Education. pp. A41–A42. ProQuest 214737425.

- ^ a b c Kleiner, Carolyn (5 March 2000). "A Push Becomes A Shove: Colleges get uneasy about proselytizing". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Balmer, Randall (2004). Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press. p. 353. ISBN 9781932792041.

- ^ Hippert, Anna Kira; Harvey, Sarah (22 December 2021). "Factsheet: New Religious Movements". Religion Media Centre. Archived from the original on 15 September 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Paulson, Michael (23 February 2001). "Campuses ban alleged church cult". Boston Globe. p. B1. ProQuest 405379940.

- ^ Michael D. Langone, Ph.D. (7 November 2001). "An Investigation of a Reputedly Psychologically Abusive Group That Targets College Students". Cultic Studies Review. Archived from the original on 7 November 2001.

- ^ Sscackner, Bill (17 November 1996). "Campus curbing of religious sects a sensitive issue". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. A-20. ProQuest 391704389.

- ^ Teale, Stacey (8 November 1998). "Churches of Christ banned from UK campuses". Sunday Mercury. p. 2. ProQuest 322115569.

- ^ Wells, Kevin S. (2004). "International Churches of Christ". In Foster, Douglas A.; Blowers, Paul M.; Dunnavant, Anthony L.; Williams, D. Newell (eds.). The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 418–419. ISBN 0-8028-3898-7.

- ^ a b Burns, M.R. (2023). "Paul's Approach to Social Superiority in the Corinthian Church Applied to Racial Superiority in the 21st Century Church". Doctoral thesis, Bethel University. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

References

[edit]- Barrett, David V. (2001). The New Believers: A Survey of Sects, 'Cults' and Alternative Religions. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 0304355925.

- Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2014). Christians in the Twenty-First Century. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781845532130.

- Jenkins, Kathleen E. (2005). Awesome Families: The Promise of Healing Relationships in the International Churches of Christ. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813536637. JSTOR j.ctt5hj239.

- Stanczak, Gregory C. (2000). "The Traditional as Alternative: The GenX Appeal of the International Church of Christ". In Flory, Richard W.; Miller, Donald E. (eds.). GenX Religion. New York, NY: Psychology Press. pp. 113–135. ISBN 9780415925709.

- Yi, Joseph E. (2009). God and Karate on the Southside: Bridging Differences, Building American Communities. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739138373.